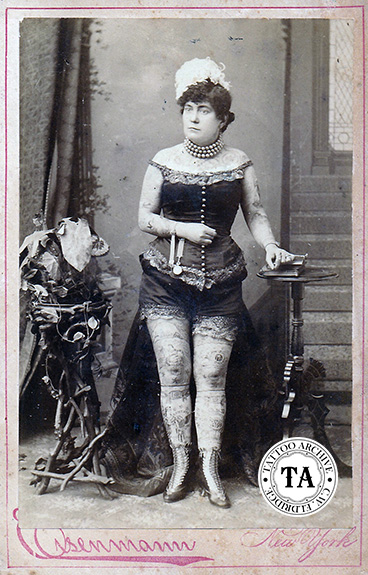

Tattooed Ladies weren’t just something to look at – they were also hired storytellers. Why did they do this to themselves? Who tattooed them? And under what circumstances? While tattooing was a normal and revered practice by many cultures and people for thousands of years, it was largely seen as scandalous and crude by a white Christian-leaning America. The origin stories of our “first” Tattooed Ladies were no exception.

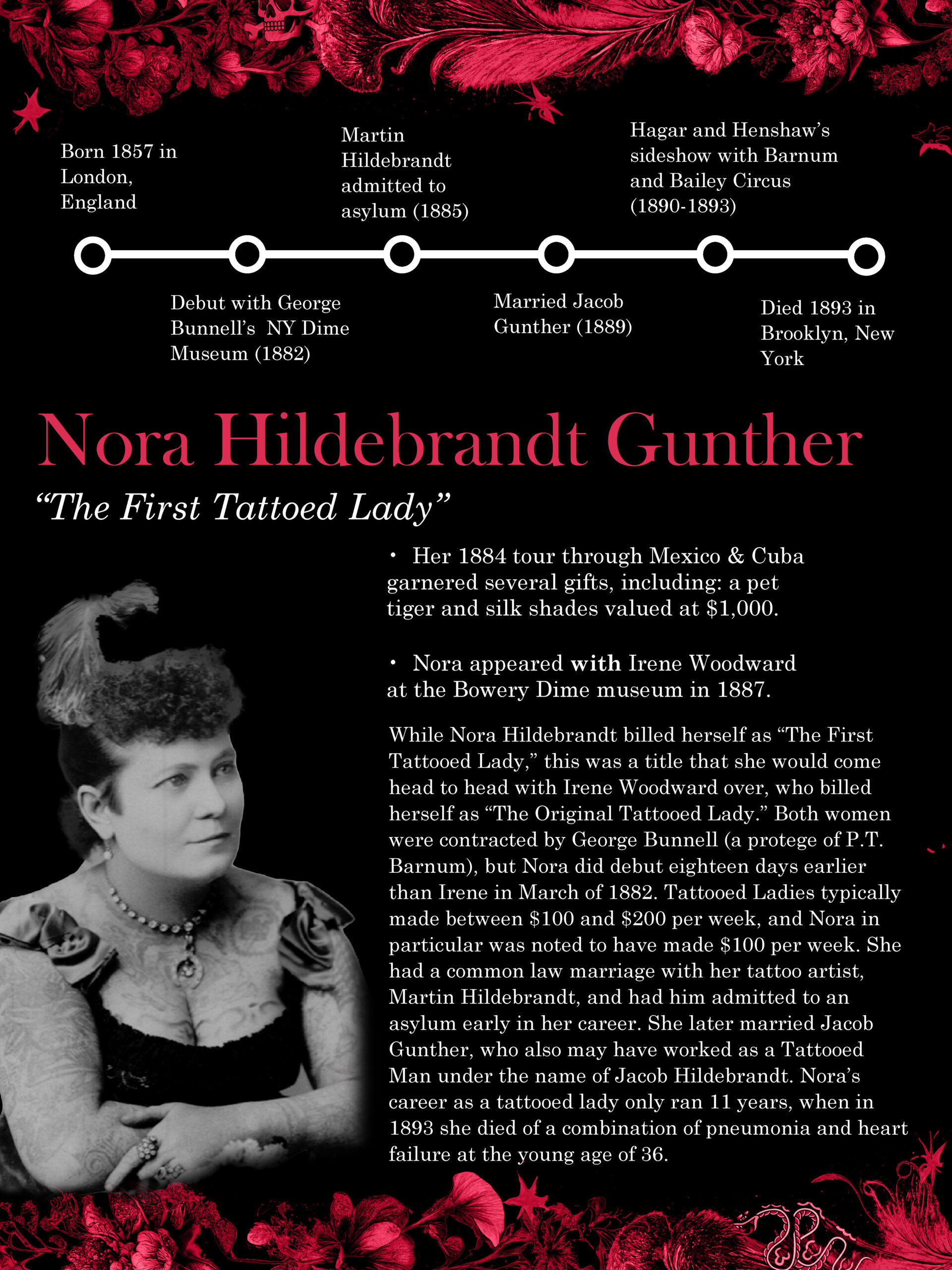

America’s sociological, economical, and literary history with captivity narratives caused centuries of irreparable harm to Native populations. Nora Hildebrandt and Irene Woodward both would have taken direct inspiration from Olive Oatman’s well known 1858 captivity account, which sold 30,000 books. Like many of these narratives, Nora’s backstory paints her as an innocent victim of tragedy to elicit pity, narrow-minded fascination, and garner people’s money – all while perpetuating the harmful racist stereotype of Native Americans as barbaric villains.

Nora’s financial success would not have escaped Irene, so their sensationalist stories were similar: while Nora was tattooed by her father in a bid for freedom from Natives, Irene was tattooed by her father as a pastime which later served as protection from Natives.

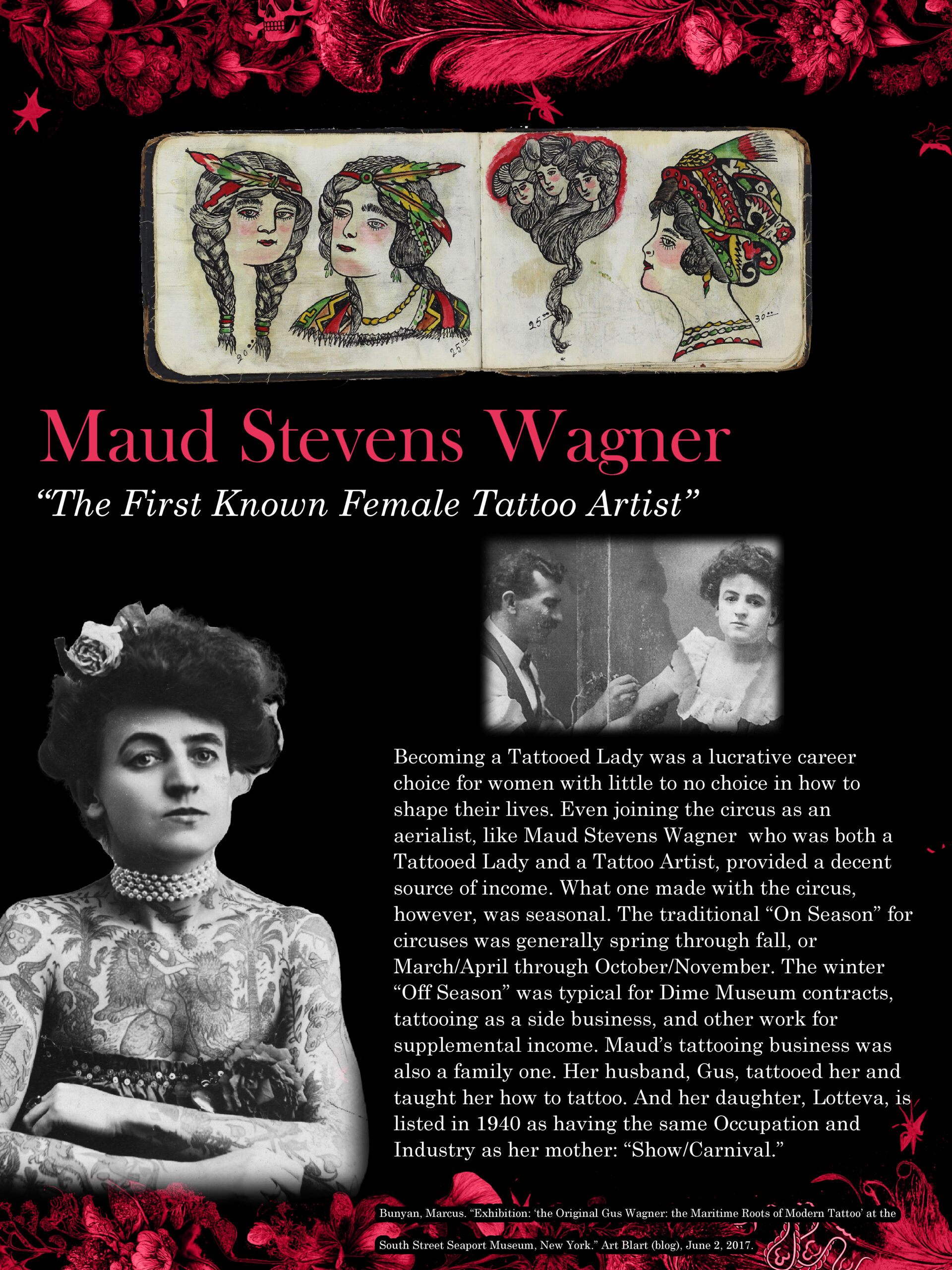

Over time, the backstory of Tattooed Ladies evolved past its racist beginnings and became more about personal choice, empowerment, and a double-down against societal norms. Neither of our first Tattooed Ladies saw the right for American women to vote (1919). Many of our later generations of Tattooed Ladies did see The Equal Pay Act of 1963 pass. But for the women who made their life’s careers out of body autonomy, few of them lived to see the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling.